I remember an egg client who called and came by to pick up a dozen last year; I think her name was Janice. She drove up to our gate and looked around, seeing the goats running by as the chickens pecked around her little Honda XUV. Their noises were punctuated by the yells of my semi-feral children, who probably weren’t wearing any clothes. She handed over the four dollar bills, folded neatly in half, and I passed her the egg carton.

She raised the carton's lid like a pirate, opening up a treasure chest to reveal its sparkling contents. Considering that our eggs are jewel-toned because of the mix of various chicken breeds we have in the flock, the smile that crossed her face seemed appropriate for the occasion.

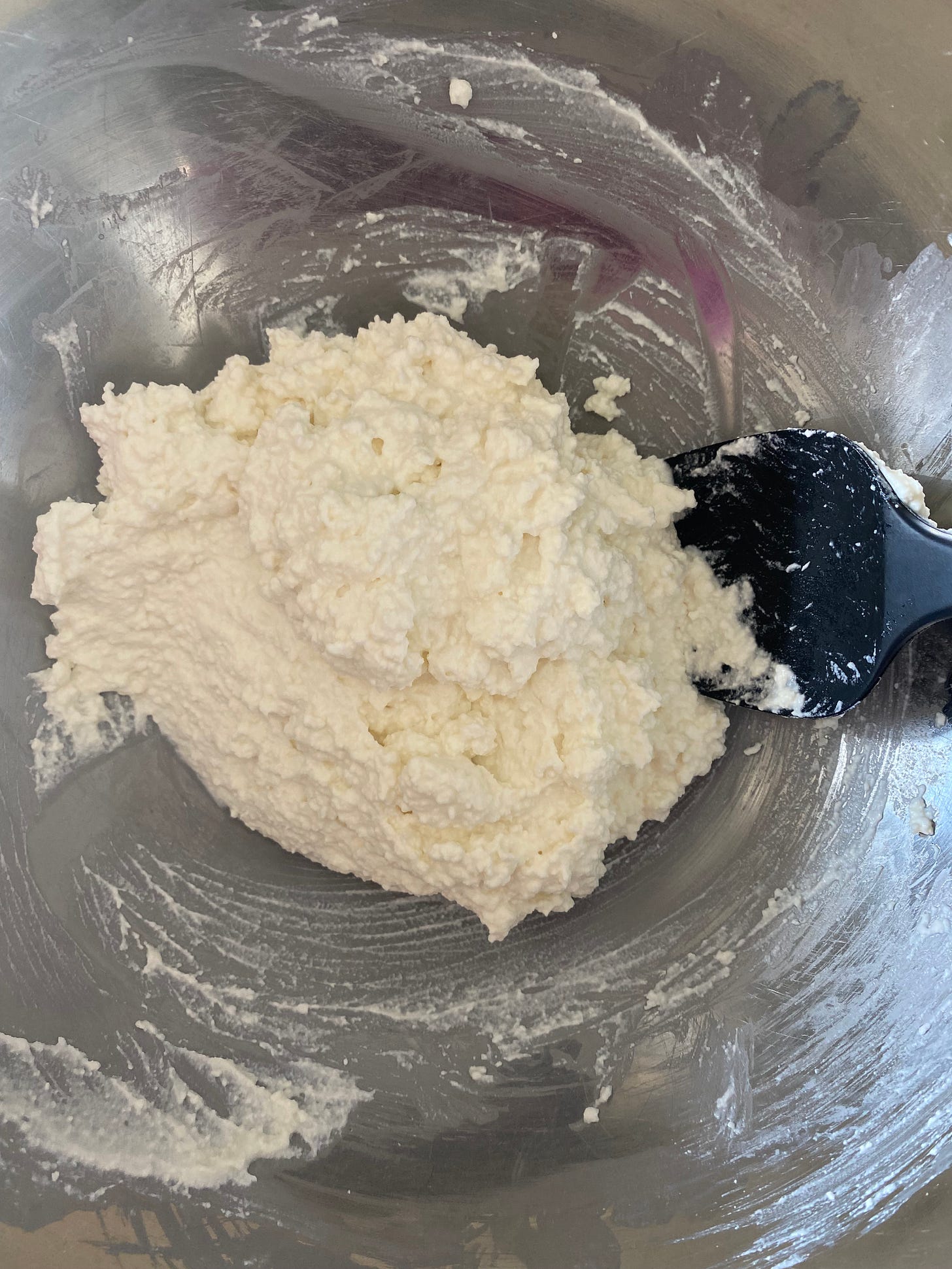

Janice seemed sweet and genuinely excited about her purchase. I love sharing what we make here on our little urban farm. When I go out to meet my friends, I'll often bring them a dozen eggs, a tub of cheese, some fresh tomatoes, flowers, or herbs.

Before turning to leave, she smiled and said: "I'm just so glad to be able to do a little something to give back and help small farmers stay afloat."

Luckily, years in media and politics have given me a better poker face than most, so rather than laugh hysterically, I smiled back and said, "We appreciate your business!"

She was so earnest and sweet, and it was such a nice sentiment, but I am sure Janice had no idea how much it costs to keep a small flock of chickens. I don't sell eggs because it makes financial sense; I sell them because I love for people in the community to share the experience with me. If I had calculated the real cost of selling her those eggs, she probably wouldn't have been an egg buyer.

Upon learning I'm an urban farmer, people love to remark about how much money must save on food. I haven't yet found ways to save on food; I've only found new ways to spend more money feeding future food.

The food produced on our little farm, whether in the gardens, egg or dairy-based, costs more than its counterparts in the store. In some cases, exponentially more. It's not that I'm a frivolous spender, quite the opposite, but there are several reasons the eggs my chickens lay will never cost as little as I sell them for:

Smaller input quantities - I probably have too many chickens right now, but my flock seems to get bigger every time I go to the feed store. Somehow a peeping box always appears in the cart as if by magic. Ultimately, though, if I have 15 chickens or 30, I still buy all the inputs for my flock in relatively small quantities.

Chicken food comes in 40 or 50-pound bags, and I buy four or five at a time. Grain for the goats is the same. Although I feel like it's a lot to load 400 pounds of animal food into my truck - compared to literal truckloads (and even sometimes trainloads) of grain and feed purchased by largescale farmers - I'm buying but a drop of water in the sea.

I'll never be able to achieve the economies of scale they have. No matter how much I buy, my feed will always be several times more expensive than larger producers.

From the goat perspective, I can't and don't buy hay by the ton, and I have to buy the small bales that I can lift and feed one at a time. Since I don't sell milk, I can only quantify the savings in the form of store milk I would have bought if not for my goats.

For me, the cost of a single bale of hay is equivalent to over 5 gallons of milk at the store . . . and my goat's conversion ratio isn't that good. It's a slow bleed, but it never quite catches up.

Infrastructure costs - Chickens don't need a lot. When I started with birds, I used a few dog houses, a shed I bought off Craigslist, and some temporary dog run panels covered with tarps for their housing. It looked more than a little tacky, like a chicken shanty town, but I wanted to ensure I was in the chicken game for the long haul before investing in something more permanent.

After I had my own eggs, it was clear that I would be a chicken tender for the long haul. We had a real chicken run built with indoor and outdoor spaces that wouldn't blow away in Colorado windstorms. Selling eggs at $4 a dozen, I will pay off that coop when I'm 536 years old.

My goats started with a single dog house, and over time I bought several Dogloos - their preferred shelter. Eventually, we built a milking/loafing shed. And since I don't sell milk, there's no chance I'll ever recover the cost of that shed.

Dumb and suicidal animals live that motley pasture life - I enjoy having chickens, but we keep a random mix of breeds. The eggs are incredible and a constant delight in our household, yet they are in no way uniform or consistent. The goats are my friends that fuel my latte and cheese addiction, but some are better milkers than others, and I will grant a lot of leeway to an animal who is better at snuggling than producing.

The cost/benefit analysis of keeping prey animals outside means that animals sometimes die, especially dumb animals like chickens who seem to try to die like it’s their job.

Animals in real business food operations are kept in conditions where they’re less likely to be eaten, stressed, drown, or disappear than they are here. No coyotes are looking through the fence at the chickens who lay eggs you buy at the store, thinking they are fluffy and delicious.

Nothing about what we do here is precise, particularly business savvy, or based on a cell containing a red number in a spreadsheet. Yet, all the food you buy at the store comes from an actual business that is run as such.

On the scale that we exist, there is little to no chance we will ever do anything other than hemorrhage money here. Yes, I can take cost-saving measures to lose money slower, but this won’t ever be my figurative nest egg. It’s a luxury, and I view and treat it as such.

Luckily, though, I love it so much that I hope it’s my literal nest egg. I will never get sick of walking out to the nesting boxes and peering over the side like a pirate spying a treasure.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t already, sign up or become a premium subscriber to help me be a goat writer!

My friend,

and I started a substack podcast to check in on what's going on at the farm and on our respective substacks. We're like your weird mom-friends with interesting hobbies. So, if you're so inclined, listen to "Meanwhile . . . Back at the Farm."Bathroom DIYs, there's not much room under a cow, and I can't believe it's no calories

Listen now (32 min) | Mary Katharine’s substack: Kelly’s substack: Mary Katharine’s bathroom reno:

Mary Katharine writes about parenting and family resilience; check out her fabulous writing:

I remember trying to crunch the numbers once, and I think I concluded that if your chickens were immortal and never got sick, you could break even after like 20 years. Now they have services where you can rent chickens to get a steady supply of eggs, lol!

I agree entirely! We have never added up the costs of building our coop & feeding our dozen chickens, who don’t lay more than a few eggs/day, but it would be laughable. It’s a lifestyle & luxury, not a money-saver. But it’s a fraction of what our two horses cost. I’d rather spend money on these animals than on nonessentials such as eating out.